The word of the day: bird

Summary

I created an automated system that texts a daily bird photograph along with a fun fact about the species. The project involved scraping an ornithology database for bird species and photos, programmatically searching the web, and using language models to generate whimsical summaries about each species. I implemented fact-checking to filter out hallucinations, and deployed the system on a low-power single-board computer to reliably deliver daily “tweets” via Twilio. This post walks through the details that brought this project to life. If you’re impatient, skip to the bottom to see the final result.

For those interested, here is the accompanying code.

Background

My partner loves birds. In fact, the first word she ever said was “bird”. Her birthday was coming up, and I decided to make her a special gift. She is quite inquisitive, so I thought she would like to receive daily fun facts about different bird species. I wanted the fun facts to contain information about where the species can be found, and some observation or behavior that could be unique to the species. I figured the most intuitive way to receive these facts was over text, so I made the goal to be to create a text messaging service that “tweets” (😁) a bird fact that includes a picture of the bird.

This post describes the process of setting up the project. To achieve this goal, I needed to set up the following things:

- Figure out how to extract the avian information I need: a list of bird species, and a picture associated with each species.

- Figure out how to programmatically run web searches to get factual information about each species.

- Facts presented as-is can be quite dry. To make it more fun and potentially digestible, I want it presented in a whimsical and (hopefully) punny style. Use a language model (LLM) to ingest the websites that contain bird facts and add style and sass.

- I expect that in many cases, facts about a specific species cannot be found because the species is rare, newly discovered, etc. LLMs tend to hallucinate in is scenario. Build a classifier to determine if the LLM-generated fact is related to the bird species.

- After completing the previous steps, the data should be ready for sending texts. Write the messaging program.

- How do I keep a server running so that I make sure texts reliably get sent daily? Set up an always-on single-board computer to run the program.

Extracting a list of bird species

Cornell University has a great ornithology lab which hosts an extensive website that catalogs over 11,000 bird species, complete with pictures and sighting locations.

I thought that this was a good place to start, since it seemed to host a majority - if not all - of the known avian species on earth. Next, I had to figure out how to extract this information from the site, and hopefully without crawling its entirety (I don’t want to affect their website’s performance).

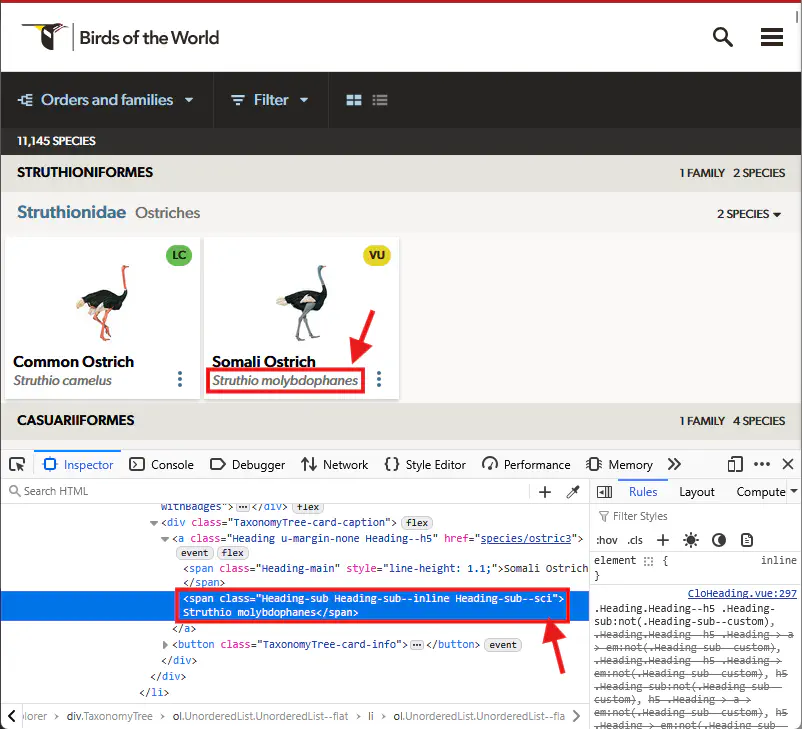

After browsing the website, I found their taxonomy explorer that lists all the genus and species in one place. It’s essentially a directory that links each bird species with an information page complete with professionally captured photographs of the bird. I inspected the taxonomy explorer’s html to see if there was anything that specifically marked the species links from other links; I found that species name links also contain the scientific name of the bird which had a special format.

This was a reliable signal I could extract. In fact, scientific names were styled with a specific class (sci). Using this I can filter out all pages not linked to a bird species.

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

# Load species list page

response = requests.get("https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/specieslist", timeout=5)

soup = BeautifulSoup(response.text, 'html.parser')

def has_sci(link: BeautifulSoup.Tag) -> bool:

"""Check if bow link contains a scientific name."""

for span in link.find_all('span'):

if any('sci' in x for x in span.attrs.get('class', [])):

return True

return False

# Filter bird species links - species pages have */species/* in URL

bird_links = [

link

for link in soup.find_all("a")

if link.get("href") and "species" in link.get("href") and has_sci(link)

]

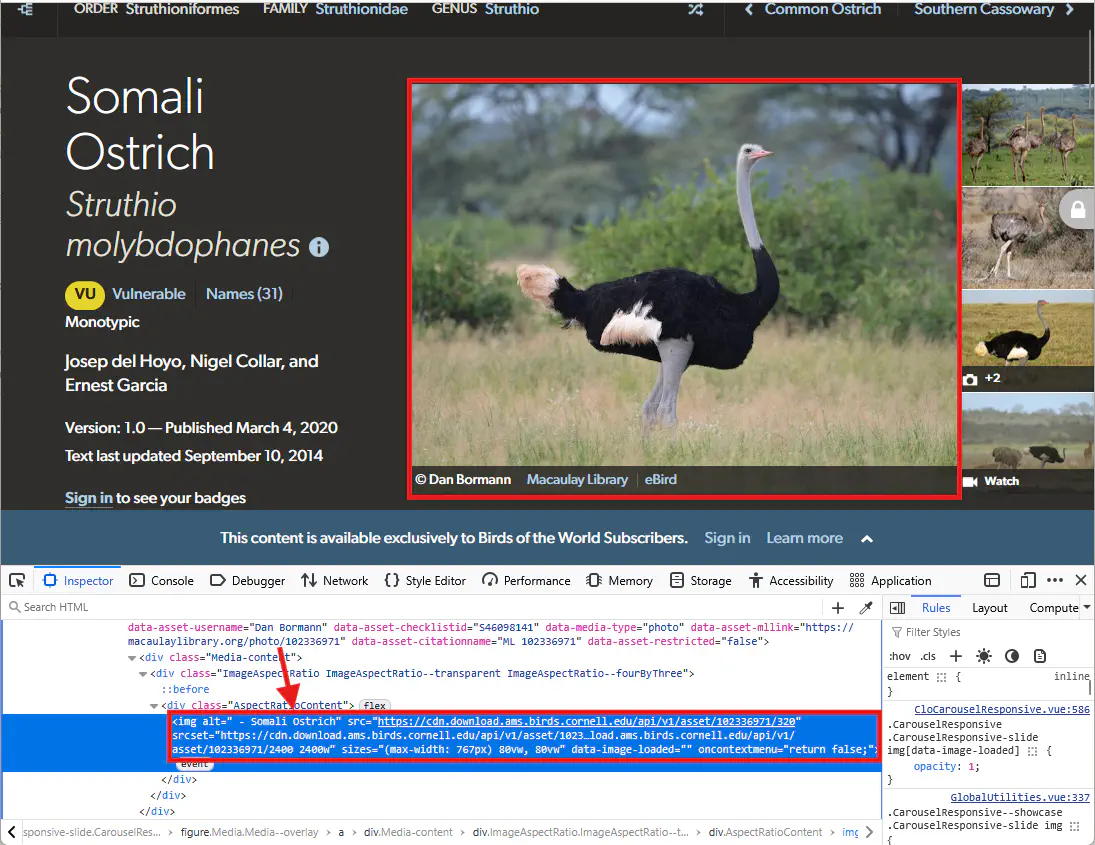

The next step was to figure out how to reliably extract a photograph of the bird. Similar to before, I loaded one of the bird species pages to look for some reliable attribute that identifies a photograph. Inspecting the HTML elements, I noticed that the img tags containing the bird photographs all had an alt attribute containing the name of the bird, and a URL that pulled a specific image resolution. All the pages I checked (way less than 11,000) had this structure.

alt text containing the species name.In code, this was a simple task. Using the URL I extracted above, I loaded the page and found the first image that used the bird name in the alt attribute and had a src pointing to an image with low resolution.

def get_bird_image_url(url, bird_name):

"""Get bird image URL for database. Returns None if no image found."""

response = requests.get(url, timeout=3, headers={"User-Agent": UserAgent().random})

if response.status_code == 200:

soup = BeautifulSoup(response.text, 'html.parser')

imgs = soup.find_all('img')

for img in filter(lambda x: bird_name in x.get('alt', ''), imgs):

src = img.get('src')

if src and '320' in src:

return src.replace('320', '480')

return None

# assume bird_names have already been extracted

image_db = {}

for bird_name, url in zip(bird_names, bird_links):

img_url = get_bird_image_url(url, bird_name)

if img_url is not None:

image_db[bird_name] = img_url

With this I had the most basic of “databases” (just a json file) with a bird name, a link to an image of the bird, and a link to its species page on birdsoftheworld.

Gathering bird facts - search engine

Half of the information gathering process is finished; the next half (generating the fun facts) is more challenging and involved. How can I reliably obtain facts about each bird species? birdsoftheworld didn’t supply this information, and I couldn’t manually search for this information for all 11,000 species of birds, so I decided to programmatically search for facts online with searxng. I tried a few simple techniques to increase the relevance of the search results:

- I used old-school search syntax techniques to ensure the name of the bird was located somewhere on the website, like:

Fun facts about bird species "Somali Ostrich"(notice the double quotes) - After receiving the search results, I filtered them to make sure the exact bird name was found somewhere in the result summary or title

- I blacklisted a few websites knowing they don’t contain fun facts, like birdsoftheworld.

Since I only needed a single fun fact, I limited the number of pages to process to at most three; I didn’t think it was necessary or efficient to use all the returned web pages. Therefore, I ranked the returned websites based on their relevance. I chose a simple ranking approach by asking a small LLM to determine the usefulness of each website for generating fun facts by scoring it with a value between 1 (not useful) and 10 (useful). See GitHub for information about the prompts.

Note: I know that re-ranking, RAG, or other NLP techniques are probably more reliable for ranking – or even extracting facts from – websites, but I didn’t want to spend the time setting up these pipelines. It turns out the approach I took was good enough.

The next step was fact generation. I cleaned and concatenated the contents from the three highest ranked websites, and added them to a prompt asking an LLM to use the website contents to generate a fun fact about the bird species, like so (see GitHub for more information):

This content for the bird species with name: {bird_name}. The

following text is from multiple websites that may or may not contain

information about the bird species. Extract information only related

to the specific bird species {bird_name}.

<text>

{text}

</text>

Use the text to tell me a unique and fun fact about the bird species

{bird_name} with puns and jokes. If the information is present, also

include where the species can be found.

“Vetting” the facts

Given that there are 11,000+ recorded species with some extinct and more endangered, it’s highly likely that some bird species have a scarcity of information. This scenario resulted in nonsensical LLM responses (like an endless list of bird species), hallucinated facts, or real facts about different bird species. In an attempt to mitigate these problems, I included a final step where I asked an LLM to judge if the fact was relevant to the bird species in question.

Here’s the system prompt:

You are an expert fact checker. Classify the supplied text surrounded in

<fact></fact> XML tags as a fun bird fact related to the species

{fact['bird_name']}. The websites used to generate the fact are provided

in XML format. Look through the websites to determine if there is in fact

any information related to the bird species. Respond with 'yes' if the fun

fact came from the websites and is related to the bird species. Respond

with 'no' otherwise. Respond in JSON.

The LLM had access to both the fun fact and the contents of the three websites to make its call. Adding this final step filtered out a small fraction of the facts generated by this pipeline.

After running all these steps, I was able to create a database with fun facts about thousands of bird species, along with a photograph of the bird.

Writing the messaging program

This was quite straightforward. I bought a phone number with Twilio and wrote a short program using Go to read in the bird facts database and send the message. The code to send the message was very straightforward:

func sendBirdMessage(client *twilio.RestClient, twilioNumber string,

phoneNumber string, birdWord BirdWord) error {

params := &twilioApi.CreateMessageParams{}

params.SetTo(phoneNumber)

params.SetFrom(twilioNumber)

params.SetBody(fmt.Sprintf("%s\n%s", birdWord.Text, birdWord.Url))

params.SetMediaUrl([]string{birdWord.Img})

_, err := client.Api.CreateMessage(params)

return err

}

I designed the program so that each time it runs, it sends a single message to each recipient. I scheduled it to run daily via cron. What’s cool about writing the program with Go is the fact it natively supports compiling a program for other CPU architectures, and is as simple as setting the GOARCH variable. This was super convenient because, as you’ll read in the next section, I needed to run this program on a computer with an ARM64 CPU architecture.

Running the program reliably

My goal was to run the program once daily at a specific time. However, I couldn’t run it on my laptop or desktop because I shut them down when I’m not using them. I wasn’t too thrilled about hosting the program in the cloud either; I was worried that I might set up the service and forget about it, potentially getting charged way more than what I set aside for this project. Finally, I wanted to keep as much of the project as private as possible.

I opted for running it on a single board computer that I had lying around – the Orange Pi Zero 3 (similar in spirit to the Raspberry Pi) which uses a low amount of power. I set up the cron job and waited until the next day to see the result.

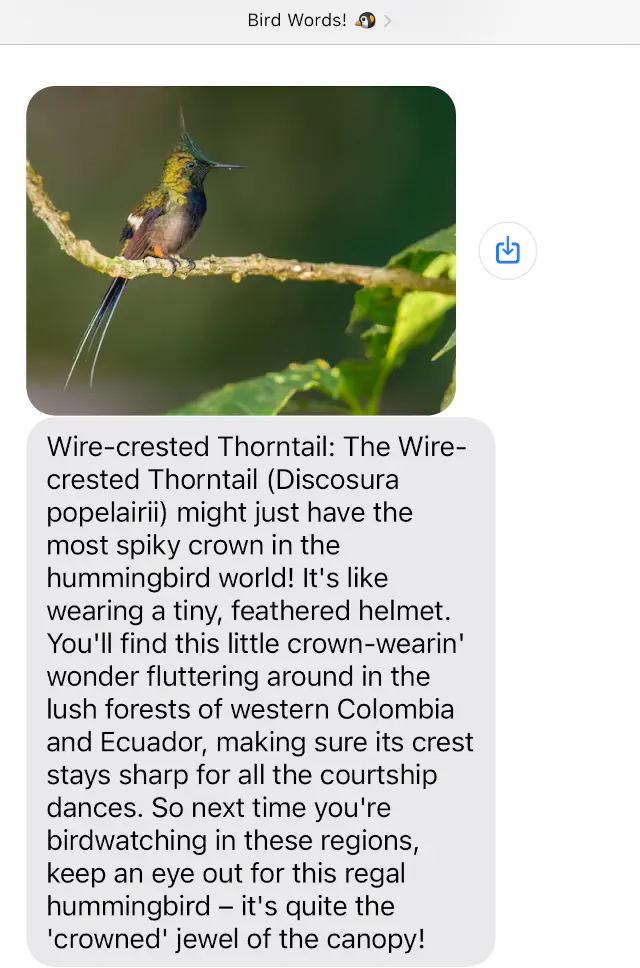

Seeing the result

Here it is! A working fun bird fact program.

Future directions

On-demand facts

I might upgrade the program to respond to incoming messages from white-listed phone numbers that request bird facts.